Those incredibly long legs became legendary, and Cyd Charisse was able to do it all—sing, act, and dance like music made flesh.

However, Tula Ellice Finklea, a slender, sickly Texas girl, was the forerunner of the woman who seemed destined for the limelight.

Her parents enrolled her in ballet “to build me up” following a polio episode, as she would later explain.

Not only that, but it also gave her life.

When Hollywood eventually called, producer Arthur Freed polished her brother’s mispronounced “Sis” into the name everyone knows: Cyd.

In Amarillo, where she was raised, wind and dust were more commonplace than footlights.

Ballet reset her compass and recreated her body.

By the time she was in her teens, she was learning from professional tutors in Los Angeles and later overseas, absorbing the classical line and épaulement that would later become her signature.

She temporarily experimented with Russian-sounding stage names during early ballet tours, as many American dancers did at the time, but the core remained the same: a calm, effortless elegance encircled by ferocious musicality.

It was dance, not conversation, that brought her to the film.

She appears first like a glimmer—specialty numbers, unacknowledged duties, that elegant female who moves in a unique way.

She was signed and allowed to mature by MGM during its imperial era.

What was to happen was indicated at by her quicksilver appearance opposite Gene Kelly in Ziegfeld Follies (1945), where her line could be heard across the room in just a few bars of choreography.

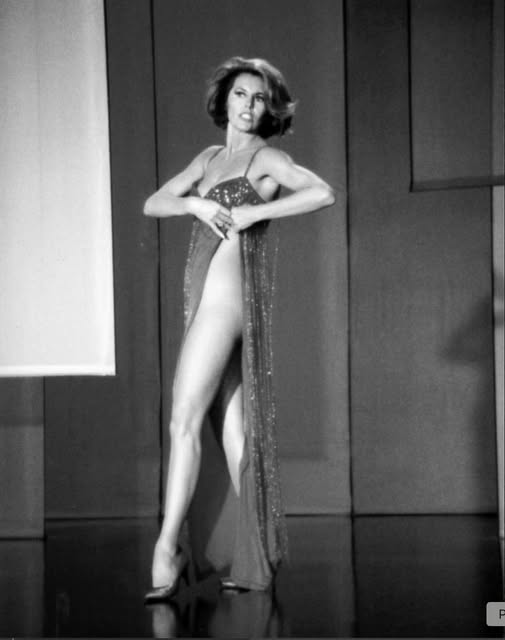

Her hair was jet black, her outfit was a poisonous shade of green, and her legs seemed to go on forever as she glided through the “Broadway Melody” ballet in Singin’ in the Rain (1952), expressing all without uttering a single word. That was the moment that cemented her in movie history.

The imprint endures even if she comes and goes like a dream.

It’s common to debate between Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire, and Charisse is one of the few dancers that enhanced both men’s already stunning appearances.

With Astaire, she could transform breath into language, and with Kelly, she could confront brute force with silk-covered steel.

“Dancing in the Dark” in The Band Wagon (1953) is essentially nothing—just two people walking into a waltz in Central Park, no trick steps, no camera acrobatics—but it feels endless because of Charisse’s contribution: her slight hesitation before giving in, the way her back tells you what her face won’t.

She was dubbed “beautiful dynamite” by Astaire.

She graciously returned the praise without taking sides, saying it would be like comparing apples and oranges.

In actuality, she responded to two distinct musical deities with equal grace.

Publicists loved to claim that her legs were insured for a million dollars by Lloyd’s of London, but that wasn’t the only thing that set her apart.

It was the wording she used to describe movement.

She didn’t dance ballet steps; instead, she breathed jazz and modern shapes until they felt natural. You could see the ballet training in any still image, including the carriage, the turnout, and the long, clean line from shoulder to wrist.

Observe how she lands a change in weight, how her foot rests on the floor like a cat, and how a turn ends with the slightest head whisper.

Charisse teaches you how to stretch, suspend, and snap time like a silk ribbon, in contrast to other dancers who sell you velocity.

Even as the musical started to falter in the 1950s, MGM kept her occupied.

Her vamp’s noir-tinged peril in Singin’ in the Rain; The Band Wagon’s cool sophistication (and sly humor); Brigadoon’s (1954) tart melancholy, where her epic line softens for a Highland romance; It’s

Always Fair Weather’s (1955) urban bite; Silk Stockings’ (1957) urbane fizz, where she updates Garbo’s Ninotchka with lethal glamour and deadpan wit; and Party Girl (1958), whose nightclub numbers doubled as character studies.

Knowing that the camera preferred to stand back and observe, the choreographers gave her space even when the script undercut her.

Off-screen, she was a studio’s dream: prepared, on time, and scandal-averse.

At a young age, she wed Nico Charisse, her former dance instructor; the couple produced a son named Nico Jr.

She wed singer Tony Martin in 1948, and their second marriage lasted for 60 years, which is nearly a Hollywood record.

Colleagues remembered the wry, quiet woman who favored orange juice over martinis, rehearsal clothes over gowns, and home over parties, even though her movie persona was all smolder.

Without self-pity, she shifted to European films, television variety shows, and finally the stage when the movie musical waned.

She and Martin performed as a sophisticated nightclub act, and in the 1990s, she dazzled Broadway crowds in the Grand Hotel with an authority that comes from years of experience.

A life touched by stardust is not exempt from suffering.

Sheila Charisse, the 36-year-old wife of Cyd’s son, was among the passengers killed when American Airlines Flight 191 crashed in 1979 shortly after it took off from Chicago.

It turned into one of those catastrophes in America that people still talk about.

It served as a reminder to Charisse and her family that poise under duress is more than just a stage act, and it left a hidden wound in their hearts that never quite healed.

Nevertheless, she continued to teach, advise, and remind young dancers that glitz without skill is just a frock.

She was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 2006, formally acknowledging what viewers, directors, and dancers have known for fifty years: that she contributed to the definition of a cinematic art form.

She suffered a heart attack and passed away two years later at the age of 86.

In 2012, Tony Martin came next.

The music continued, but their lengthy duet did not.

Examine these three instances carefully if you want to know what she did that no one else does:

She dances as if she were a satin-wrapped blade in “Broadway Melody” (Singin’ in the Rain).

The well-known green dress is choreography rather than only a costume.

The bias cut transforms each step into a line drawing, and the slit exposes the engine.

It reads surrender when she folds into Kelly’s arms, but notice how her spine never gives out.

Softness is a power choice

The Band Wagon’s “Dancing in the Dark” – No fireworks.

Simply breathing, followed by an inevitable walk.

What the lyric cannot convey is that love is rhythm, not argument, as demonstrated by the way she stretches out her leg and lets the heel kiss the pavement.

Title number for “Silk Stockings”: Charisse uses silence as a weapon.

The control is fierce; the humor is deadpan.

After revealing the soldier inside the satin, she shares your laughter.

Her presence has broader ramifications than just the set pieces.

Hollywood’s standard choice for a leading lady in a musical prior to Charisse was “ingenue who can move.”

Following Charisse, choreographers began composing for a woman who was not just an ornament but the center of the dance language, capable of carrying it as Astaire did.

Editors learnt to cut less, partners learned to listen, and directors learned to let the camera linger.

She created room for the upcoming generation of dancers, who weren’t scared to be complex, modern, or statuesque.

The deeper truth is preferable, even though the myths—the emerald dress that started a thousand crushes, the cool hauteur, and the million-dollar legs—are entertaining.

Strength can appear like silk, elegance can be athletic, and a story can drop softly and precisely on the beat after traveling down a calf and across an ankle, as demonstrated by Cyd Charisse.

The movies are still humming decades later.

Turn the park into a ballroom by putting on The Band Wagon.

You may witness the green dress edit itself into your memory by playing Singin’ in the Rain.

See how a raised eyebrow may be choreographed in Silk Stockings.

You only need eyes to appreciate her, not nostalgia.

Movement was her language.

Her legacy continues to dance.